Personal Spirituality

As in most Protestant churches, we recognize two things as "means of grace" or actions that we can take that can be points where God can shape us and through which we can gain strength and wisdom. These two "means of grace" are prayer and Bible study. A third activity that is essential to our growth in character and spirituality is service to others.

Prayer

Prayer, as we're going to discuss it here, is more than just talking to God. Personal prayer is also about listening, about being quiet with God and being prepared to have the contradictions in your life and the teachings and stories of the Bible to bubble through your mind and reorganize into challenges to you and challenges for you to bring to the larger church.

Many of my personal heroes in the history of people of faith were women and men who became convinced during their prayer time that the way the church and the world had been doing things for centuries was wrong. When Cotton Mather wrote the pamphlet The Negro Christianized, in 1706, he shocked the people of Massachusetts by teaching that God is color blind and doesn't prefer one race over another. It was such a controversial view at that time that he was afraid to have his name printed on the pamphlet because of his fear of the backlash from his neighbors, his congregation, and even his own family. He didn't come to believe that position by reading someone else's argument. He got there through his own quiet reflection on what he was reading in Scripture and what he was seeing in the world around him. It is my hope that each of us would have the courage to sit quietly as a part of our devotional life and then be willing to share with the wider community what we learn in that silence. It is quiet conversions in history like what happened in the heart of Mather that have changed the church's view of slavery, of racial justice, of women in public ministry, and the inclusion of sexual minority people. These quiet conversions when sitting quietly with God may be the only way the God moves the Church forward.

If my own life is any indication, We are often tempted in our prayer lives to make God into some sort of divine Santa Claus. We go in prayer with a wish list of things we want, like a greedy child at Christmas.

We are indeed invited to bring our needs, our fears, and our hopes to God in prayer, but prayer is for more than merely asking for things. When I teach about prayer to younger children, I use the five letters A, C, T, S, and I (a letter for each finger) to teach about what to include in prayer. The letters stand for

- Adoration: "I love you, God. You are great because . . . ."

- Confession: "God, I'm sorry for . . . ."

- Thanksgiving: "Thank you, God, for . . . ."

- Supplication: "Please, God, give me . . . ."

- Intercession: "Please, God, my friend needs . . . ."

The list of your requests still has a place (supplication), but it is accompanied by other kinds of relating to God which helps keep you from making prayer just a self-centered "gimme" time.

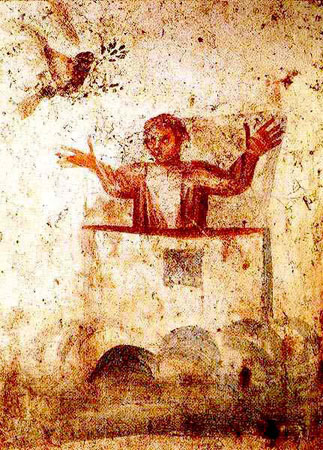

Your posture when you pray is sometimes a question. Some people choose to pray in a specific posture: kneeling with eyes closed and hands folded, or rocking your whole body as in some forms of Jewish prayer. As Presbyterians we do not prescribe any specific posture, but we do understand that most of us struggle to stay appropriately attentive during prayer. For many of us kneeling or closing the eyes and folding the hands just helps us stay more focused on what we're doing. I often pray while driving on the long rural sections of the interstate. I obviously need to keep my eyes open and my hands on the steering wheel, but I also know that I am often distracted from the flow of my prayer by the scenery or the traffic. Some people choose to help themselves focus in personal prayer in their homes by focusing on candles or using incense or quiet music. Whatever works for you and helps you organize your thoughts is great. The problem for most of us is not how we pray but that we pray regularly enough.

Bible Study

Allegorical Method

An allegory is the description of one thing under the image of another. It is the exact opposite of a literal discourse.

[The word "allegory"] is used only in Gal. 4:24, where the apostle refers to the history of Isaac the free-born, and Ishmael the slave-born, and makes use of it allegorically.

Every parable is an allegory. Nathan (2 Sam. 12:1-4) addresses David in an allegorical narrative. In the eightieth Psalm there is a beautiful allegory: "Thou broughtest a vine out of Egypt," etc. In Eccl. 12:2-6, there is a striking allegorical description of old age.

(Easton's Bible Dictionary)

In allegorical study, we keep track of the many images and symbols that are used to represent other things. For instance a dove often represents the Holy Spirit. The number twelve often represents the tribes of Israel or the twelve apostles. The number seven often is a reminder of God's perfection. The number three is often a reminder of the trinity. These allegorical associations are not something you can master by simply reading a book about symbols in the Bible. Only after reading and re-reading the Bible and in reading sermons and commentaries from throughout our history, can a student begin to get a handle on the many allegories used in Scripture. A major problem with the allegorical method is that some students, and more than a few preachers, begin to see every number, every animal, and every plant as representing something else. Although it is true that there are many allegories, metaphors and similies in the Bible, sometimes things are just simply what they appear to be. Most modern Christians do not believe that the Bible is written in a secret code that can only be interpreted by scholars who've received some hidden knowledge. Usually allegories are either explained within the text or are easy to understand in the passage's context. More often than not, the truth of a passage is restated in the allegories and metaphors. For instance in Psalm 23, the message that God cares for us is beautifully restated with the image of God as a shepherd and the writer as a sheep. The allegory does not hide the passage's meaning, but reinforces it.

Historical-Critical Method

The historical-critical method is the most common method for studying the Bible today. In this method, the student asks who was a particular passage in the Bible written for and what was the cultural expectation of this writing by its first audience. When a student of religion studies the original languages of a Bible passage or uses information from archaeology to help interpret a passage, she is using the historical-critical method of interpretation. This method also studies the changes or differences that are evident within the pages of Scripture. For instance there are sometimes differences among Matthew, Mark, and Luke in describing the same event. The historical-critical method asks why these differences exist and what they tell us about the perspective or theme the writer is working with.

Scripture was written over a long period of time by a variety of writers who wrote in styles appropriate to their time and place. One aspect of the historical-critical method is the analysis of how different types of writing assume different expectations from the readers. For instance, today you read an email much differently than you read a novel or a recipe. When you see the script of a play printed in a book you have learned how to read it and visualize the play in your head. When we read Scripture we need to ask, "Is this a letter? Is this a history record? Is this a poem? Is this a sermon?"

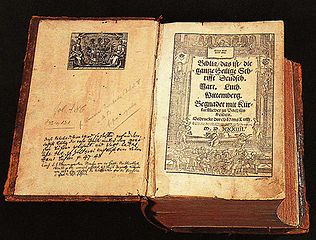

Bible Translations

The Bible has been translated from its original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek into the languages of people throughout the world. The first translation into English was by John Wycliffe in the 14th Century. Since that time, there have been many more English translations. One of the most familiar, the Authorized Version, informally called the King James Version, was commissioned by James I of England to bring an end to the heated debates about which version to use in the churches of his kingdom. It was translated by scholars representing all of the factions within the Church of England at that time. When it was published in 1611, King James ordered that it was to be used for reading in the churches and that there would be no more controversy over which translation of the Bible was best.

Although the language of the King James Bible did a good job of reflecting the formal speech of England in the 17th Century, changes in speech patterns, words falling out of common usage, and changes in the meanings of certain words have made it more difficult to understand with every passing generation. This increasing difficulty has led to the creation of the sometimes confusing variety of translations, versions, and paraphrases available today.

The job of the women and men who produce the translations and paraphrases of the Bible is

- to reveal the dynamic meaning of the original texts

- to recreate that dynamic meaning in language that can be understood by a modern audience

- to write the final version in smooth memorable language that can be easily read aloud in public worship

The translations (or versions) most frequently used by Presbyterians in worship services are the Revised Standard Version, the New Revised Standard Version, and the New International Version. These are considered excellent modern translations that are faithful to the original texts. They were also written in a style that makes them comfortable to read in public. An example of a version of the Bible which translates strictly and retains the original passage's grammar even when the result is somewhat awkward English is the New American Standard Bible. An example of a paraphase which focuses on the message and relaxes its hold on the grammar and specific words of the original passage is the Good News Bible.

In your personal study, I suggest you use whichever version you feel the most comfortable with and that you understand the best, but also consider several other translations and paraphrases when a passage seems unclear. A great number of English translations are available online. The important thing is that you listen for the Word of God when you read and study the words of any translation, paraphrase, or version of the Bible.

One major, and often controversial, part of the historical-critical method of interpretation involves the assumption that the Bible books we have today were often compiled or even rewritten over several generations. This part of the study analyses the changes that the different generations made and asks why. Sometimes it is easy to identify the additions because the later writer used words in a language that did not exist in the days of the original writer (for instance an Aramaic word inserted into a Hebrew passage). The controversial part of this theory is that the different generations of editors or redactors seldom identified their changes. It is always possible that the student will organize the changes according to what he wants to see rather than what can be positively identified as a later addition. For instance, if I don't like something Paul wrote, I might claim it was added by another writer years later.

In Presbyterian churches, we usually use the historical-critical method of interpretation. We try to be aware of the archaeological and cultural background of the passage, we try to be aware of the literary form of the passage, and we keep our minds open to the possibility that the passage reflects more than just one person's or one generation's understanding of what God was doing. But we also use the allegorical method from time to time. For instance, we often refer to Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. This is a reference to the Passover story from the book of Exodus. Its use makes the Passover story from the Old Testament an allegory of the story of Holy Week.

Literalism

At this time, we should also discuss what is meant when conservative Christians refer to their method of interpreting the Bible as "literal" as opposed to how liberal Christians interpret the Bible. Some Christians (conservatives and liberals) will even go so far as to declare that anyone who does not interpret the Bible exactly the way they do is rejecting the Bible altogether and probably is not really a Christian at all. Never forget, whether or not someone is a Christian is dependent on God's love and Jesus life, death, and resurrection and not because of how an individual interprets a handful of Bible verses. I interpret the Bible about as literally as a conservative Christian. We both recognize the figurative language and limits of historical context in the Bible. On most of these points we usually agree.

Figurative Language

It is important to remember that even when you are visiting with your friends you recognize a host of different figures of speech. If one of your friends said after hearing a joke, "You kill me!" You don't go running to get a policeman or a paramedic. (You'd more likely check to see if your friend has fallen through a time warp and was speaking from the 1950s.) Historically, people in their teens and twenties do a lot of playing and experimenting with language and use a huge amount of metaphoric language. In the period when the New Testament was written, it was quite common for writers and public speakers to use a host of rhetorical devices and figures of speech that extended far beyond simple literal declaration. Nearly all Christians agree as to which passages in the Bible should be taken as figurative language and which are literal.

Context

Practically all Christians believe some passages do not apply today as they may have in their original, ancient context. There is a very large area of agreement on which passages fit in these categories. Few Christians today, would agree that it is acceptable for parent to have a child killed because he is disobedient to them as is ordered in Deuteronomy 21:18-21. When Psalm 137, which celebrates killing an enemy's infant children, is read alongside Jesus' instruction to love our enemies, most Christians readily agree that Jesus' words should be held as more authoritative than a text about joyfully smashing open the heads of babies. This belief that certain passages in Scripture are more authoritative today is mostly accepted by liberal and conservative Christians alike.

Divisions

It is, however, common to divide Christians into conservatives and liberals on the basis of how they interpret a handful of passages. These passages usually apply specifically to how women's lives and ministry are to be appreciated; how people of different races, language groups, or economic needs are to be served and included; and how sexual minority (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) persons should be valued, served, and included. As liberal Christians, we most often differ with conservative Christians about certain passages of Scripture because of how we interpret the whole of Scripture including certain passages which talk about inclusion (for instance Acts 8, Acts 10, and Galatians 3) which we believe have authority over less welcoming passages.

Remember when someone says they take the Bible literally what they are usually saying is that they interpret a small group of passages differently than we do. They may also be implying that they are better Christians because of their choices against women's rights, against the needs of the poor, and against sexual minority persons. Make no mistake, if you aren't in a good relationship with God, forget about the conservative/liberal stuff and fix your relationship with God immediately. However, merely adopting someone else's method of interpreting a few verses in the Bible will never make you closer to God.

If you are troubled by disagreements about something in the Bible, consider that a challenge to spend more time reading the Bible and thinking through things for yourself. It's your life and it's up to you to figure out what you believe and why. Ultimately you are the only one in charge of your relationship with God. I hope you'll choose to accept and enjoy God's love despite all the evil messages and cruel actions prevalent around us. Please don't let another person's opinions about a couple of sentences give you doubts about how much God already loves you.

God's love is always there surrounding and embracing you and me and everyone else (even our enemies), but we sometimes put up barriers that keep us from enjoying that love. For instance

- if we have absorbed someone else's negative, hateful words about us

- if we have allowed jealousy or greed to overwhelm our sense of right and wrong

- if we are full of hate and resentment

- if we are unwilling to love and respect others

- if we see the needs of our neighbors and decide to ignore them

God's love for us is already there. We just need to get rid of the negative stuff that keeps us from enjoying it. To put it into more traditional religious language, if you want to experience salvation, turn away from sin.

Service to Others

Christianity is a matter of word and deed. What we say only has value if it is matched with our actions. That is the obvious importance of our service to others. It is important for us to give money and volunteer our time to make sure others are housed, fed, educated, and cared for; however, another very important, maybe even more important, reason to serve others is less obvious.

When we serve others, particularly when we see with our own eyes persons with specific physical, financial, and social needs, we are changed. When we serve alongside those who are recovering from a disaster like a hurricane, we experience their pain and build a bond with them that changes us. When we provide clothes, housing, or food for those in financial need, we begin to understand the economics of community at the heart of our faith. When we visit with persons in a hospital or in a nursing home and share friendship and emotional support in places we might otherwise avoid, we give the Holy Spirit the opportunity to bubble through our hearts and to reorganize our priorities, values, and choices. Service to others helps us develop empathy and sympathy for the needs of others. These emotions are the roots of the type of love that characterizes mature Christianity.

It is important to serve because it gives our hearts an opportunity to be transformed. Yes, we absolutely must take the physical, financial, and social needs of our neighbors seriously, but the change in our own hearts and in developing our own character may be even more important in the greater scheme of things than the immediate service we provide. Christianity is about much more than what we believe or what we say, it is about growing past the selfish, greedy, childish focus on our selves that we were born with to focus on the needs and concerns of others and eventually to be in love with others. Our goal is to love others not because they are like us, or are close to us, or are going to love us back, but because love is of God.