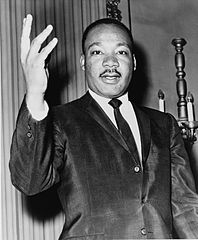

Martin Luther King, Jr.

During the 20th Century

King enrolled in Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1944. He wasn't planning to enter the ministry until he met Benjamin Elijah Mays, the president of Morehouse College, who convinced him that a religious career could be intellectually satisfying. After receiving his bachelor's degree in 1948, King attended Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania receiving his doctorate in 1955.

King returned to the South to become pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. He made his first mark on the civil-rights movement, by mobilizing the black community during a boycott of the city's bus lines. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, a black seamstress, had been arrested for refusing to give her seat up for a white man as required by city ordinance. The black community boycotted the buses for 382 days. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court declared bus segregation unconstitutional.

King worked to keep his protests nonviolent both as a Christian principle and as a matter of strategy. He wanted to change wrongs not create new ones. His speeches display his passion for the promise of the gospel and of the Declaration of Independence. He did not wish to harm his enemies but to convert them to an understanding that the equality taught in the Bible and promised in our structure of government could be a blessing to both his allies and his enemies. King's home was bombed during the boycott. His life was threatened many times, and he was arrested. Still, the Montgomery Bus Boycott is considered the first great nonviolent demonstration in the United States.

In 1957 he was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization formed to provide new leadership for the growing civil rights movement. The ideals for this organization King took from Christianity, but he developed its operational techniques from the example of Mahatma Gandhi of India.

In the spring of 1963, he led a massive protest in Birmingham, Alabama, that caught the attention of the entire world, providing what he called a coalition of conscience. and inspiring his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" which responded to the criticisms of local religious leaders that African Americans should peacefully wait for change. In August of that year, he directed the peaceful March on Washington of 250,000 people to whom he delivered his best known address, "I Have a Dream." from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

In January 1964, Time magazine designated Dr. King as its Person of the Year for 1963. A few months later, he was named recipient of the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. King's activities and the public awareness his protests (and international publicity) caused led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which overturned a host of forms of discrimination.

By 1967, King had become involved in the protest against the American war in Southeast Asia. His "Beyond Vietnam" speech at the Riverside Church in New York City is a demonstration of his connection between fighting injustice and Christianity. He was always a preacher, always a minister, never merely an activist. The activism he is remembered for was always related to his understanding of the gospel.

In the eleven-year period between 1957 and 1968, King traveled over six million miles, spoke over twenty-five hundred times, was arrested upwards of twenty times, and assaulted at least four times. In the same period, he wrote five books as well as numerous articles. On the evening of April 4, 1968, while standing on the balcony of his motel room in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was to lead a protest march in sympathy with striking garbage workers of that city, he was assassinated.

King wrote in an article for the magazine Redbook in September 1961:

"I am first and foremost a minister. I love the church, and I feel that civil rights is a part of it. For me, at least, the basis of my struggle for integration-and I mean the full integration of Negroes into every phase of American life-is something that began with a religious motivation.

King may be known to the larger world for his accomplishments in opening economic opportunities to African Americans and for helping many others begin to recognize the evils of racism. But for the Church, Martin Luther King's greatest legacy may be his work to convert those around him to the belief that Christian faith is not only about how we honor God but also how we treat and love our neighbors. He understood that respect for other persons—even for our enemies—is central to our response to the Gospel.